Scientific Modelling: Prologue

Created by Pavl_G

Scientific Modelling is a robust rocket-science way of miniaturizing real systems in order to examine, predict, and/or enhance specific phenomena, and based on the underlying theory, one can derive the relations and the way the internal components interact together in a scientific space.

Scientific Modelling is utilized in almost all human sciences including biomedical, engineering, and research fields.

Definition of Scientific Models

Scientific Models: are miniaturized structures that idealize specific phenomenological systems, the idealization process involves modelling the specific system phenomena of interest using the underlying scientific theory, and decomposing the system into components, then skeletonizing an entity structure that modularizes and groups related components from a universe set, the system. The relations between components and one another are mapped based on the underlying theory; hence, we can deduce the following terminology legend:

- A phenomenon: represents a factual entity designating the output/s of a particular system, these factual entities could be observational or conclusional data (e.g., the alignment of planets in-close-proximity to the Sun in Solar System that is a mere description of a factual observation in a system).

- A theory: represents the underlying scientific laws, rules and/or infrastructure that build and influence the interaction between components and themselves in a system (e.g., the Newtonian physics in the alignment of planets in-close-proximity to the Sun in the Solar System).

- A model: represents a miniaturized form of the system designed to examine and study a specific part of the phenomena in a realized system (e.g., the interaction of Earth with the humanitarian satellites and their orbital forces in the Solar System).

- Raw data: is the explicit plain output data from a model pipeline before passing to model filters.

- Processed data: is the implicit ouput after being processed by model filters (e.g., decoded data, decrypted data, model adapters data structures).

- Parameters: are input values to the model that miniaturizes a specific system, they control the model behavior and states, and thus the output, there could also be raw (or preprocessed) parameters and processed parameters.

- Experiments: are another models that idealize the main model to concretize specific parts of that model and to test and validate it (e.g., Simulation Models).

Types of models:

House of scientific models:

| The House of models |

|---|

|

|

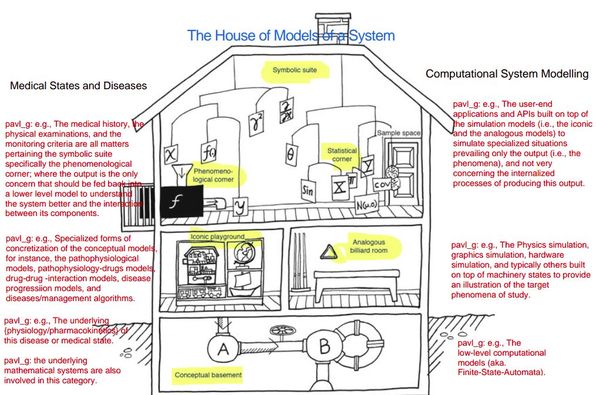

This illustrative diagram depicts a full image to the different types of scientific modelling together with their specific level-of-details (LoD), and the variable indifference in the essence of two highly applicable sciences nowadays, Internal Medicine V.S. Computational Systems (disclaimer: it’s not really a Versus relationship, it’s just for applying some humor to the topic!). The diagram of concern is represented as a house of models to specify the essentiality of abstraction levels (aka. LoD or level of details), in which the most accurate models lie in the basement; as where the infrastructure resigns, the strong building parts are aligned.

The house of models is subdivided into 2 floors excluding the basement, but including the ceiling. The design typically starts with the “Conceptual Models” at the basement, those are very system-abstract in nature, and provide high level of details for the target system, a great example of these are the “Mathematical and Physical Models”. On the second floor resides the “Iconic Models” and the “Analogous Models”; those concretize the conceptual models into further objectified structural and behavioral matters that map the components and relations of a given system in a more specialized way, very oriented to the system in-study or in-commission. On the last floor, aka. the ceiling, resides the most system-oriented layer of modelling, the “Symblic Models” with its both types, the “Phenomeno-logical Model” and the “Statistical or Stochastic Models”, both of which having common interests prevailing the study of phenomena of a system, aka. the output of a group of theories. In conclusion, to model the phenomena of a system, it’s better to start with a symbolic model and move all the way down to provide LoD as it essentiates, while to model the interaction between two or more components or a component and its internalized states, it’s better to start with the iconic model and move up and down as it essentiates. On the other side of the spectrum, the conceptual models are deemed to the very specific needs of studying systems with a higher level of details to better predict outcomes of the target systems. However, of notice, the stochastic models and the mathematical models can be integrated in a one conceptual model!

The spectrum of modelling is a very heavy topic, and cannot be covered easily in one documentation manual, but it’s really handy to put these stuff in mind in parallelism to what we study in everyday life, it differs too much if your approach is too scientific as compared to that bad faulty ad-hoc maneuvers.

I’ve a lot of energized determination to show you how scientific modelling could be used in software engineering specializing in system engineering and design; as it uncovers the unrevealed components of systems, and maps the relations among them, and at the same time, utilizing the same models in describing medical states, diseases, approach, management, and monitoring.

The Computational Model on the right side: provides a layered approach to integrate all the runtime environment aspects starting from the basement, where OS and HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layers) resigns on the bare-metal CPU and board modules, moving to the application and API user-ends, and passing by specialized binaries and dependencies that specialize the OS and HAL interfaces for a specific purpose in-mind, taking into considerations, the interaction between them.

The Medical Analyzer Model on the left side: provides a layered approach to integrate all the medical sciences, in addition to mathematical models at the basement, to describe a single system (e.g., Medical State, Disease, or even a Surgery).

Notice, that sometimes some information is irrelevant to a specific system, and so this necessitates to omit specific layers of modelling while manifesting others, this is known widely in modelling as the “selectivity of system parts” including the phenomena and the underlying theories we are trying to model.

Construction of Models

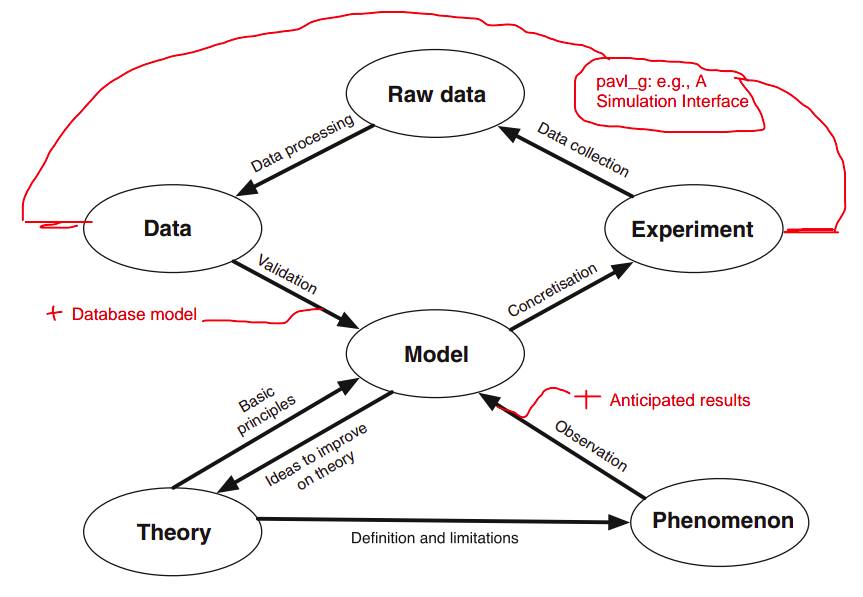

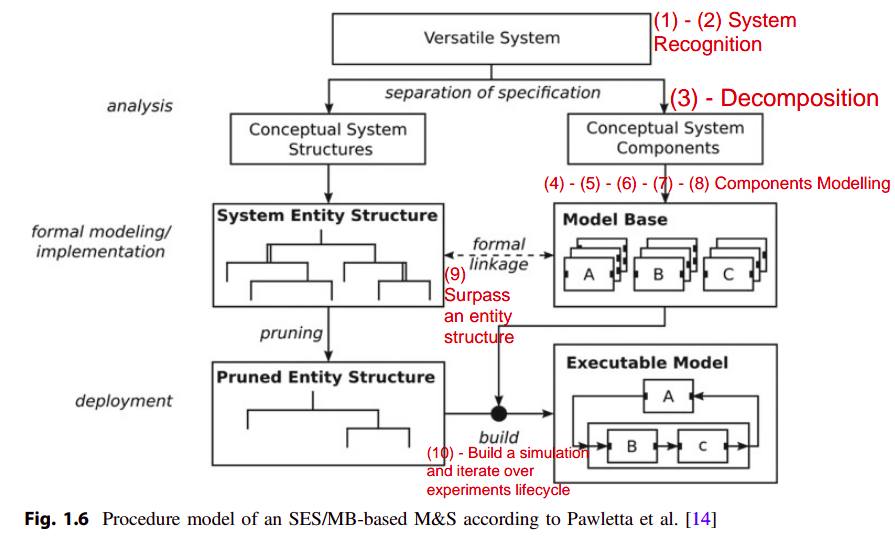

There are several maneuvers for bringing a scientific model into life for a specific system, for instance, the System Entity Structure Framework (SES) aka. the Entity-Component System in software design, and the Tricotyledon System Design (T3D) introduced by Wymore which utilizies the set theory and ports automata to the design of the system behavior. One way is introduced here is the System-Entity-Structure Framework (SES) according to Pawletta T, Durak U, Schmidt A together with some insights from Wymore’s T3D (Fig-1.7).

| Constructional Usage |

|---|

|

|

| System-Entity Structure Framework (SES) |

|---|

|

Practical Steps in building a model (iconic, conceptual, and symbolic parts) and validating it:

1) Examining the phenomena of interest.

2) Finding or deriving the theories underlying this specific phenomena.

3) Recognition of the system infrastructure in which this phenomena occurs.

4) Decomposing the system of interest into primitive components (Set Theory Applied).

5) Finding and deriving relations between the decomposed components using the underlying theory.

6) Finding and deriving conditional relations between components (Propositional Calculus Applied).

7) Grouping the decomposed components into modules (modularization, Group Theory Applied).

8) Apply Step.05 and Step.06 on modules derived from Step.07.

9) Surpass modules into Entities.

10) Specialize entities objects into simulation environments.

11) Data collection and processing from the simulation environments.

12) Feed the data back into a comparing interface.

13) Validate the model based on Steps.10-11-12 with Steps.04-05-06.

14) Re-iterate and improve the model and the understanding of the underlying theory.

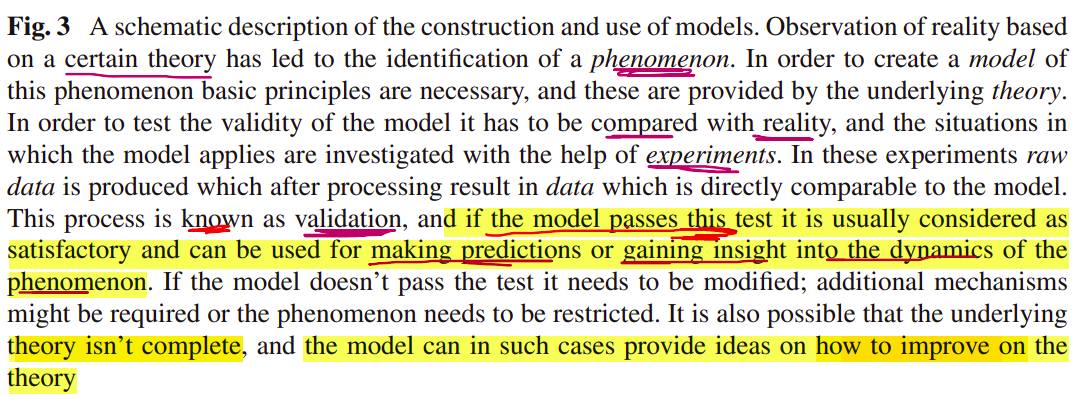

Notice, how (Fig-1.7) references the steps in this text, and those steps are coincident with (Fig-3) which conveys the structure and the relation between the various components in scientific modelling and not the process steps per se.

=> References:

Our Features

Distributed Simulation

An overview of distributed simulation systems.

NASA DSES Project

Insights into the Distributed Space Exploration Simulation System project of NASA.

Educational Applications

How educational institutions can benefit from simulation systems.

Scalable Solutions

Implementing scalable solutions for various needs.

Contacts:

Name

Pavly Gerges

pepogerges33@gmail.com

Tel

Address

Egypt, Cairo